Close-up and Cinema

Main Reference: Mary Ann Doane, ‘The Close-up: Scale and Detail in the Cinema’, Differences, 14.3 (2003), 89–111 https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-14-3-89.

Tags: #cinema #Montage #Eisenstein #Epstein

Reference at the front from Main reference, at the end from second reference메리 앤 도언의 The Close-up: Scale and Detail in the Cinema는 영화에서 클로즈업이 갖는 역사적·이론적 중요성을 분석하며, 특히 엡스테인(Epstein), 에이젠슈테인(Eisenstein), 발라즈(Balázs), 들뢰즈(Deleuze) 등의 논의를 바탕으로 클로즈업의 의미를 탐구한다.

클로즈업 이론의 기원은 **1920년대 프랑스 인상주의 영화(French Impressionist cinema)**로 거슬러 올라간다. 이 시기 영화 이론가들은 photogénie라는 개념을 도입하며 이를 영화적 특수성을 정의하는 핵심 요소로 간주했다. Photogénie는 언어를 초월하며 영화만이 표현할 수 있는 본질적인 요소로 여겨졌지만, 이 개념 자체는 이론적으로 일관되지 않았다 (Doane, 2003, p. 90).

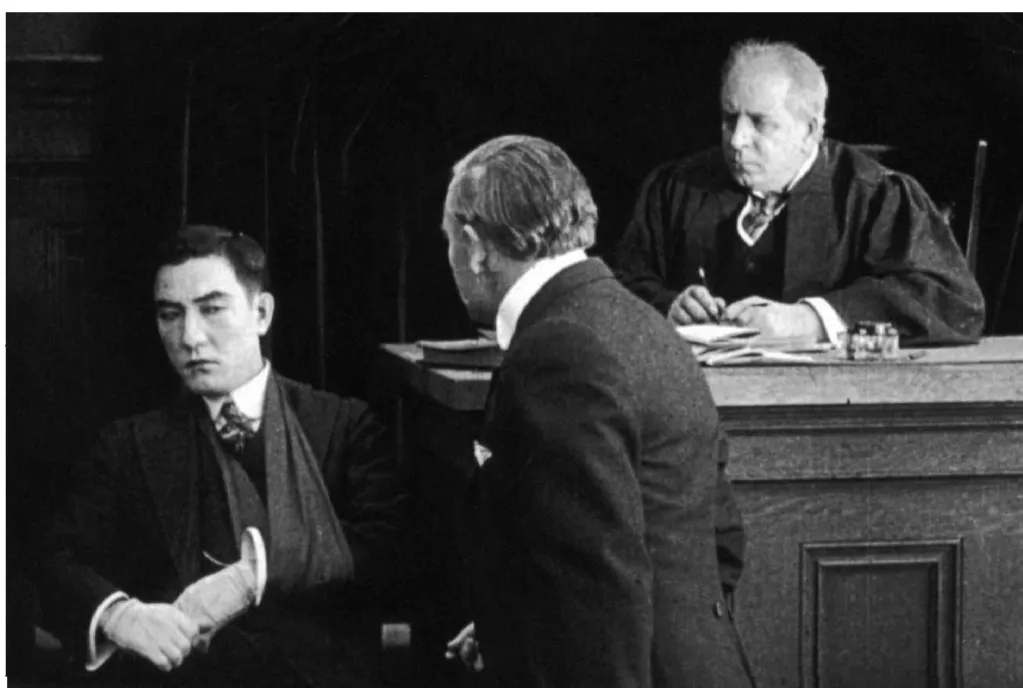

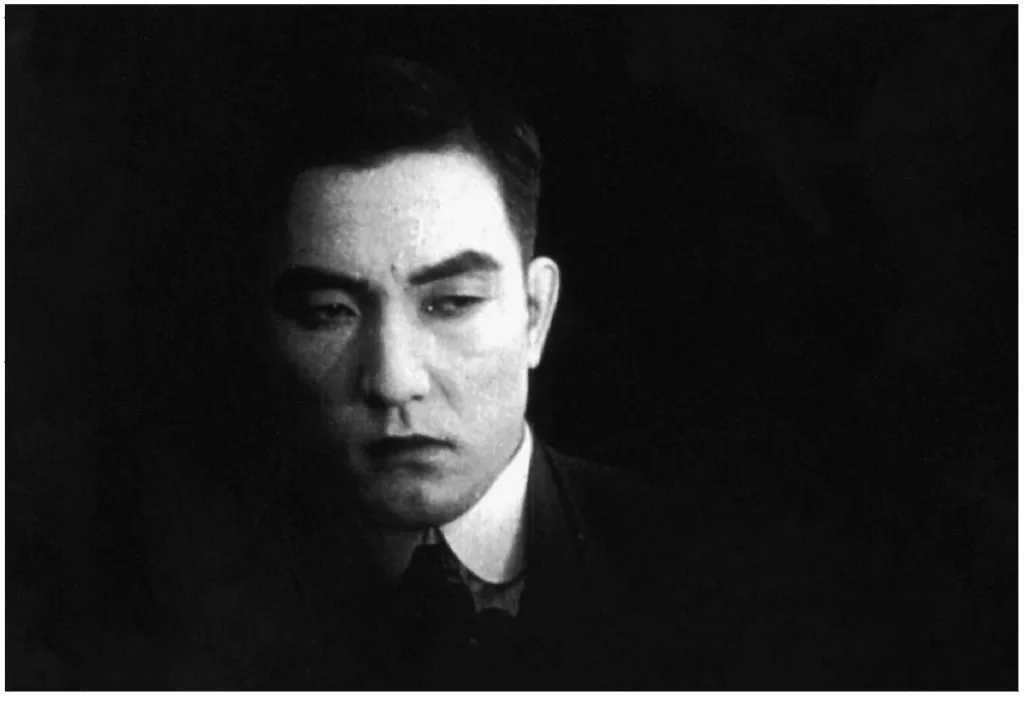

엡스테인(Epstein)은 클로즈업을 영화적 수행의 규범 속에 위치시키며, 이를 통해 이미지가 도덕적 성격을 강화하는 방식을 강조했다. "나는 필름적 재현을 통해 도덕적 성격이 강화되는 사물, 존재 또는 영혼의 모든 측면을 포토제닉(photogenic)이라고 설명할 것이다." (Bonjour, 20). 엡스테인에게 클로즈업은 얼굴을 단순한 주체성의 자리에서 이질적이고 낯선 객체로 전환시키는 도구였다. 또한, 클로즈업은 세부적인 요소, 우연성, 특이성을 강조하며, 관객을 이미지의 미세한 요소까지 세밀하게 들여다보도록 유도한다 (Doane, 2003, p. 90).

클로즈업은 기본적으로 자율적인 존재이며, 영화의 전체성에서 분리된 하나의 **독립적인 단위(fragment)**로 작용한다. 엡스테인은 클로즈업을 하나의 반(反)서사적 장치로 보았으며, 이로 인해 클로즈업은 영화적 담론의 통일성을 위협하는 반(反)기호적 요소로 작용할 가능성이 있다고 지적했다. 클로즈업에서 가장 빈번하게 등장하는 피사체는 인간의 얼굴이지만, 이 과정에서 얼굴은 신체로부터 분리되며, 마치 단두대에 의해 잘려나간 것처럼 보인다 (Doane, 2003, p. 90–91).

- Jean Epstein, Le Lion des Mogols, Jean Epstein, 1924, Provenant de la collection : La Cinémathèque française

- Epstein’s extravagant language, perhaps unconsciously and certainly despite the invocation of morality, delineates the close-up as a lurking danger, a potential semiotic threat to the unity and coherency of the filmic discourse.

- 가장 많이 쓰이는 클로즈업은 = 얼굴 the face, fragments the body, decapitating it

클로즈업은 서사적 시간과의 관계를 변화시키는 역할을 한다. 클로즈업을 통해 화면 속 공간은 얼굴이나 오브젝트에 의해 "소진"되며, 이는 순간의 시간이 확대되는 대신 서사적 시간의 흐름이 희생되는 방식으로 작동한다 (Doane, 2003, p. 91). 이러한 시간과 공간의 재구성은 영화 이론에서 중요한 논쟁의 대상이 된다. 들뢰즈(Deleuze)는 벨라 발라즈(Béla Balázs)의 논의를 인용하며, 클로즈업은 단순히 오브젝트를 전체로부터 떼어내는 것이 아니라, 이를 모든 시공간적 좌표로부터 추상화하여 "존재(Entity)"의 상태로 승격시킨다고 주장한다. "클로즈업은 오브젝트를 그것이 속했던 집합으로부터 찢어내는 것이 아니라, 오히려 그것을 모든 시공간적 좌표에서 추상화하여 '존재'의 상태로 상승시킨다." (Deleuze, 2018, p. 106).

발라즈(Balázs)는 클로즈업을 "영화 예술의 기술적 조건" (qtd. in Aumont, p. 84)이라고 보았고, 엡스테인은 클로즈업을 "영화의 영혼"(Epstein, Magnification, p. 9)이라고 표현했다. 한편, 에이젠슈테인(Eisenstein)은 클로즈업을 몽타주의 필수 요소로 간주하며, 이를 비판적이고 지적인 영화의 핵심 요소로 보았다. 그는 그리피스(Griffith)가 표현을 "표면적 재현"의 수준에 머물게 한 점을 비판하며, 클로즈업이 반드시 "추상적인 표현"을 가능하게 해야 한다고 주장했다.

"여기서 다시 동일한 결함이 나타난다: 현상을 추상화하지 못하는 것, 그리고 이러한 추상화 없이는 그것이 좁은 재현의 영역을 넘어 확장될 수 없다." (Eisenstein, 1977, p. 243).

에이젠슈테인에게 클로즈업은 단순히 보여주거나 제시하는 것이 아니라, 의미를 부여하고, 지칭하며, 기호적 의미를 생산하는 도구였다. "소비에트 영화에서 클로즈업의 기능은 단순히 보여주거나 제시하는 것이 아니라, 의미를 부여하고, 지칭하며, 기호적 의미를 생성하는 것이었다." (Eisenstein, 1977, p. 238).

영화에서 클로즈업의 개념은 문화적 맥락에 따라 다르게 정의되기도 한다. 러시아와 프랑스 영화 전통에서는 클로즈업이 웅장함과 스케일의 확장을 의미하는 반면, 영미권에서는 근접성과 관객의 시점에 초점을 맞춘다. "러시아와 프랑스의 클로즈업 개념은 '삶보다 더 큰(larger than life)' 이미지를 창조하며, 도달할 수 없는 스케일을 보장하는 반면, 미국에서는 근접성과 관객과의 관계에 초점을 둔다." (Doane, 2003, p. 112).

발터 벤야민(Walter Benjamin)은 클로즈업을 소유욕과 연결된 요소로 해석하며, 영화의 재현성이 관객이 물리적으로 도달할 수 없는 대상을 "가까이 가져오고자 하는 욕망"을 반영한다고 설명했다. "현대 대중이 사물을 공간적으로나 인간적으로 '가까이 가져오려는' 욕망은 그만큼 강렬하며, 모든 현실의 고유성을 복제의 수용을 통해 극복하려는 성향이 존재한다." (Benjamin, 1936, p. 223).

반면, 크리스티앙 메츠(Christian Metz)는 언어학적 접근 방식을 통해 클로즈업을 단순한 독립적 장치가 아닌, 더 큰 영화 언어 시스템 내의 하나의 요소로 보았다. 그는 영화 이미지가 항상 실현되는(actualised) 속성을 지닌다고 주장하며, "영화에서 권총의 클로즈업은 단순히 '권총'을 의미하는 것이 아니라, '여기에 권총이 있다!'라는 문장적 의미를 전달한다." (Metz, 1991, p. 67).발라즈는 클로즈업을 인간과 사물을 동일한 사진적 재료로 변형시키는 요소로 보았으며, 이는 특히 무성 영화에서 강하게 나타난다. "영화 클로즈업이 우리가 보지 못하는 것들을 보여줄 때, 결국 그것은 인간 자신을 보여주는 것이다. 사물에 인간의 감정을 투사하는 것이기 때문이다." (Balázs, 1970, p. 60).

이러한 논의에서 클로즈업은 단순한 확대의 개념을 넘어서서, 영화적 체험과 의미 생성의 핵심 요소가 된다. 도언은 클로즈업이 단순한 시각적 요소가 아니라 신체적 감각과 맞닿아 있는 체험적 요소라고 분석하며, 이를 통해 영화가 어떻게 완전성을 향한 욕망과 그 불가능성을 동시에 만들어내는지 설명한다.

"클로즈업 속에서 영화는 전체성을 향한 욕망과 그 불가능성을 동시에 다룬다. 이는 신체적 경험과 맞닿아 있으며, 촉각적 감각과 같은 차원에서 체험된다." (Doane, 2003, p. 109).

결국, 도언은 클로즈업을 미학적, 기호학적, 정치적 요소가 결합된 개념으로 분석하며, 이것이 영화 속 얼굴, 오브젝트, 그리고 스케일의 개념을 어떻게 변화시키는지 설명한다.

(For Epstein) Sessue Hayakawa’s face In Cecil B. De Mille’s 1915 The Cheat – Given the stony immobility of his face, a slight twitch of an eyebrow could convey extraordinary significance.

- Rouben Mamoulian, Queen Christina, 1933.

Mary Ann Doane’s essay, The Close-up: Scale and Detail in the Cinema, examines the historical and theoretical significance of the close-up in cinema, situating it within key debates in film theory, particularly those of Epstein, Eisenstein, Balázs, and Deleuze.

The origins of close-up theory can be traced back to French Impressionist cinema in the 1920s, where the term photogénie emerged as a concept central to the cinematic experience. Photogénie was often described as the essence of cinema, something that exceeds language, and was thus considered its most cinematic quality. However, this concept remained theoretically incoherent (Doane, 2003, p. 90). Epstein defined photogénie as belonging to the norms of cinematic performance, stating, "I would describe as photogenic any aspect of things, beings or souls whose moral character is enhanced by filmic reproduction" (Bonjour, 20).

For Epstein, the close-up had the potential to transform the face, stripping it of its subjectivity and turning it into something alien and fragmented. It isolates minute details, contingencies, and singularities, inviting the spectator to scrutinise them in a way that was previously impossible (Doane, 2003, p. 90). The close-up is thus an autonomous entity, a fragment that exists "for-itself," distinct from the film’s totality. Epstein’s rhetoric suggests a sense of unease, as if the close-up, in its radical reconfiguration of scale, posed a semiotic threat to the unity of cinematic discourse. The face, being the most frequently used subject in close-ups, undergoes a violent fragmentation, detaching it from the body as though decapitating it (Doane, 2003, p. 90–91).

The close-up functions semiotically by suspending linear narrative time. The screen space is “used up” by the isolated face or object, and the moment of contemplation expands at the expense of linear temporality (Doane, 2003, p. 91). This reconfiguration of time and space in the close-up has significant implications for cinema theory. Deleuze, drawing on Béla Balázs, argues that the close-up does not simply detach an object from its surrounding context. Instead, it abstracts it from all spatio-temporal coordinates, elevating it to a state of Entity: "The close-up does not tear away its object from a set of which it would form a part, but on the contrary, it abstracts it from all spatio-temporal co-ordinates, that is to say it raises it to the state of Entity" (Deleuze, 2018, p. 106).

For Balázs, the close-up represents "the technical condition of the art of film" (qtd. in Aumont, p. 84), whereas Epstein describes it as the "soul of cinema" (Epstein, Magnification, p. 9). Eisenstein, on the other hand, saw the close-up as essential to montage, a means of producing an intellectual and critical cinema. He criticised Griffith for failing to abstract beyond "narrowly representational" images, arguing that true cinema must move beyond literal representation:

"Here is the same defect again: an inability to abstract a phenomenon, without which it cannot expand beyond the narrowly representational. For this reason we could not resolve any ‘supra-representational,’ ‘conveying’ (metaphorical) tasks" (Eisenstein, 1977, p. 243).

Eisenstein’s Soviet cinema employed the close-up not merely to show or present, but to signify, designate, and produce meaning: "The function of the close-up in the Soviet cinema was not so much to show or to present as to signify, to give meaning, to designate" (Eisenstein, 1977, p. 238). His concept of the close-up involved "absolute changes in the dimensions of bodies and objects on the screen" (Eisenstein, Au-delà, p. 229). The power of cinematic perspective is such that "a cockroach filmed in close-up appears on the screen one hundred times more formidable than a hundred elephants in a medium-long shot" (Doane, 2003, p. 112).

Beyond Soviet cinema, different linguistic and cultural traditions conceptualise the close-up differently. The Russian and French terms emphasise scale and grandeur, invoking an overwhelming sense of largeness, whereas English terminology focuses on nearness and proximity, shaping the spectator’s perspective and relationship to the image. The Russian and French terms reject possession in favour of transcendence—the image is truly “larger than life,” a scale that guarantees unattainability (Doane, 2003, p. 112).

Walter Benjamin connects the close-up to desires of possession, suggesting that the reproducibility of film allows audiences to symbolically "get hold of an object at very close range" (Benjamin, 1936, p. 223). In contrast, Christian Metz, applying linguistic theory, argues that the close-up functions less as an independent cinematic unit and more as a syntactic component within a larger system. Metz claims that in film, the image is always actualised. He differentiates between langage (language system) and parole (speech acts), stating, "A close-up of a revolver does not mean ‘revolver’ but at the very least, and without speaking of the connotations, it signifies ‘Here is a revolver!’" (Metz, 1991, p. 67).

Balázs sees the close-up as fundamentally anthropomorphic, whether applied to human faces or objects. He writes, "When the film close-up strips the veil of our imperceptiveness and insensitivity from the hidden little things and shows us the face of objects, it still shows us man, for what makes objects expressive are the human expressions projected onto them. The objects only reflect our own selves" (Balázs, 1970, p. 60).

Aumont describes the close-up as producing a surface that is simultaneously legible and sensory, a process that, in Deleuze’s terms, raises the image to a state of Entity (Aumont, p. 85). The close-up renders its subject quasi-tangible, generating a strong phenomenological experience of presence. However, this presence is paradoxically also a sign, a surface that demands to be interpreted. "The close-up transforms whatever it films into a quasi-tangible thing, producing an intense phenomenological experience of presence, and yet, simultaneously, that deeply experienced entity becomes a sign, a text, a surface that demands to be read. This is, inside or outside of the cinema, the inevitable operation of the face as well." (Doane, 2003, p. 94).

Deleuze radicalises this by stating: "As for the face itself, we will not say that the close-up deals with it or subjects it to some kind of treatment: there is no close-up of the face, the face is itself close-up, the close-up is by itself face and both are affect, affection-image" (Deleuze, 2018, p. 88).

Film theory frequently grapples with the opposition between surface and depth, exteriority and interiority. Balázs describes the face as a universal language, arguing for "the universal comprehensibility of facial expression and gesture" (Balázs, 1970, p. 44–45). According to Deleuze, the face historically functioned in three key roles:

- As the site of individualisation, representing a person's uniqueness.

- As the manifestation of social roles and types.

- As the medium of intersubjectivity, enabling communication (Doane, 2003, p. 95).

However, the close-up dismantles these roles, detaching the face from its social function. It forces the spectator beyond individuation and interpersonal exchange, creating a crisis of meaning. The resulting nostalgia for silent cinema arises from the fact that, in that era, "it is the face that speaks, and speaks to us so much more eloquently when mute." (Doane, 2003, p. 96).

The close-up simultaneously generates desire for totality and its impossibility. Its enigmatic nature aligns with photogénie, one of the earliest manifestations of cinéphilia, celebrating the unique ability of cinema to produce a form of incomparable ecstasy (Doane, 2003, p. 109).

Doane’s analysis ultimately reveals how the close-up, while often assumed to be a purely cinematic technique, operates at the intersection of aesthetics, semiotics, and politics, shaping how we perceive the face, objects, and cinematic scale itself.